ABOUT JASPAL JANDU

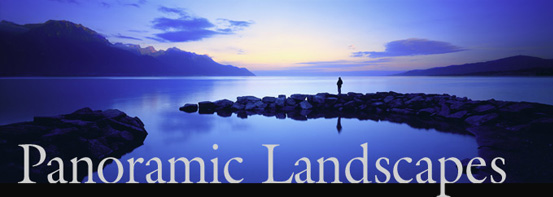

Jaspal Jandu is a respected photographer based in London, England. Often travelling to remote parts of the world, he passionately believes that landscape photography is a crucial part of the environmental debate. Jaspal primarily shoots with a large-format, panoramic film camera and his work is characterised by sweeping vistas and epic light.

Jaspal recently provided the following interview to Sophie Martin-Castex at UK landscape, one of the UK’s premier websites for landscape photography.

What is your background?

Through various studies and jobs, I have been involved in and surrounded by fine art and music throughout my life. Apparently, it is often said that playing music creates new pathways in your brain that stimulate creativity.

More formally, I majored in economics and it’s something which I still enjoy to this day. There's a great quote from Leonardo Da Vinci which states that one should aim to "...study the science of art and the art of science". I guess in this vein, it's healthy keeping one part of my brain active with photography and the other with something completely different now and again.

Why did you choose to be a landscape photographer?

My father was a prominent architect and I clearly remember being fascinated by the bewildering blend of art and science in his study room. After contemplating a similar career myself, I eventually chose to pursue a different discipline which could provide me with an equally rewarding mix of art and craft.

Eventually, as I began to travel with my camera I started to mature, both personally and professionally. My previously embarrassing attempts at photography were soon crystallising into something more solid and the ratio of ‘keepers’ to ‘losers’ was increasing dramatically.

It was during this growth spurt that I began to realise how important and overlooked landscape photography is to the environmental debate. Returning to countries again and again, I would compile almost time-lapse images of, for example, glacial retreat and desertification. Given the resonance of such images with the general public and art editors alike, I eventually resolved myself to a career in landscape photography.

Is your dedication to landscape a way to resist modernity?

I am always enthralled by the intrinsic paradox of the natural world; its ability to remain timeless in the face of remorseless change.

By way of illustration, let me compare it with the cities in which we increasingly dwell. My fascination with architecture led to me to shoot many cityscapes in the early days. However, I soon realised that no matter how much care and attention I paid to the images (please don’t mention camera movements and converging verticals), they were always dated within a year or so. Compare and contrast this with landscape photography. One can view the 19th Century plates of pioneers such as Carleton Watkins and still feel the immense grandeur of Yosemite Valley despite the immense change in the environment over the intervening years.

What is your current project?

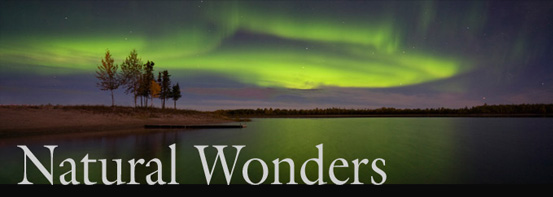

main focus at the moment is publication of a new book entitled Natural Wonders: A Panoramic Vision. It covers over 25 countries on earth and highlights the fragile state of the world’s ecosystem and our shared destiny within it. It has taken over 4 years to complete and all the images are presented in my preferred panoramic format.

What events can we expect?

I am currently promoting my work via exhibitions and corporate tie-ins (recently holding a collaborative with Porsche, AG) whilst continuing to shoot new material. The website - www.jaspaljandu.com - is doing extremely well and the ultimate aim is to tie this in with a dedicated gallery of my work in the not-too-distant future.

What set this whole thing off? A rebellion? A disappointment? Or simply the pleasure of taking your readers on a voyage?

Many years ago, I began to seriously immerse myself in disciplines such as geology, meteorology and oceanography. It was soon painfully evident that Mother Nature had an imagination far more powerful than any human. Whether it be underwater waterfalls in the Denmark Straights, electrical discharge from the Andes or coloured rain from the Sahara, I simply wanted to break out of my studies and get on a plane as soon as possible.

As I started travelling, I began to construct an internal narrative based around the Confucian concept of interconnectivity. For example, the complex mixing of the Equatorial and Humboldt currents off South America not only affects the local fishing and tourism industries but it also drives the powerful El Niño and La Niña weather systems. In turn, small 'malfunctions' in either of these two phenomena have a more than a commensurate effect on countries as far away as Australia.

Ultimately, this narrative became so compelling that I simply had to share it with others.

Did you have to prepare yourself for this journey, if so for how long and how?

The journey itself has taken around four years with the single continuous stretch of around one and a half years. Being based in England, it has been relatively easy to take cheap flights to, say, Scotland or the Alps. Given that everything is so accessible in Europe, I often find that there is not really that much to prepare for.

Most of Africa was completed in one rather long and adventurous visit. Starting in Tanzania for Mount Kilimanjaro and the Ngorongoro Crater, the voyage went on to the Serengeti (Kenya), Drakensberg (South Africa), Sossesvlei (Namibia) and Victoria Falls and Mana Pools (Zimbabwe). As I was also shooting digitally by this stage, my main worry was battery power and memory storage. I was also concerned about camera safety and sand/dust but in the end both of these issues proved to be easily surmountable.

The long continuous trip of 18 months was much more difficult because of the geographies and climates involved. It took about two months to agree the schedule and pack the gear (packing swimming trunks alongside snow crampons was interesting). I ended up producing a huge hand-drawn map with all the natural wonders accompanied by the seasons, visa requirements, flight time tables and the like. By the time it was time to leave for the trip, I honestly felt equally exhausted as I did excited.

Where you given sponsorship or did you self fund this?

The entire project was self-funded. However, now that the project is gaining momentum, I have had a number of parties approach me to do something together in the future, so watch this space…

How big a crew did you take?

Short trips to Europe were easily be handled by myself. Longer trips to places such as Everest and Africa involved joining a specialised guide or group at the respective destination. I was accompanied by my partner (Teresa) for a large part of the long road trip of 18 months. Photographers are a curious breed of individuals who generally have higher highs and lower lows than most, so I am eternally grateful for her patience and fortitude behind the scenes!

What gear did you use, and film stock?

I’m not really a ‘gear-head’ and am always at pains to point out that a camera is ultimately a tool which helps us to communicate our hopes, thoughts and desires to others. However, having said this, I am also cognisant of the fact that photography is a craft and therefore relies heavily upon the tools of the trade.

To this end, my primary camera is the Linhof 617 SIII. In terms of ruggedness, usability and sharpness, I have found nothing comes close. Although I tend to favour the use of both the Super Angulon 90mm and 72mm lenses (equivalent to ~19mm and ~15mm respectively in 35mm terms), I also use the 180mm lens for more telephoto / abstract work. Fuji Velvia 50 (both 120 and 220 formats) is the colour film of choice with Tmax 100 used for black and whites. I have tried the new Velvia 100 Professional and found it not to my liking (particularly its handling of the red spectrum) so I am currently using the new Velvia 50 II. A Sekonic light meter, Lee filter set and Manfrotto tripod round off the main tools.

Latterly, I have also begun using Canon digital cameras. A variety of lenses accompany me including the 14mm, 17-40mm, 24-105mm and 100-400m. Having both the Linhof and the Canon is really a dream combination. Whilst the former handles epic landscapes in its stride, the latter comes into its own with fast moving and/or variable ISO scenes. Covering every known biome - forest, aquatic, desert, grassland and tundra – in the course of my journey, I can personally vouch for how good modern cameras have become.

What was the biggest catastrophe and what was the happiest moment on the trip?

The single biggest set-back occurred in Venezuela. As I was attempting to capture the grandeur of Angel Falls, a rumour began to spread that I was a journalist from National Geographic who was overtly photographing local people without the necessary permits. Needless to say, having the Minister for Indigenous Affairs and four armed guards pounding on my bedroom door at 4am in the morning wasn’t the most pleasant of experiences. After a fairly heated debate, I managed to get all of my camera gear back but by then I had lost crucial shooting time in my very short stay in the country.

My fondest memories are of touring the American Southwest. Hiring a camper van and traipsing though such awe-inspiring scenery such as Canyonlands and Monument Valley should be standard rites of passage for everyone. Not only did it yield some literally jaw-dropping pictures but it also convinced me that the best photographs are made when the connection with the land is at its strongest.

Did the scope of the project and the sights you witnessed teach you anything about yourself and your skills? Do you feel this has changed you in any way?

Given the size and scope of the journey, it was inevitable that I would change during the course of it. Professionally, I think I am getting to the point where I am more worried about the art and not the craft. There’s a universal four-stage model of learning which may help to explain my thinking:

1. Unconscious Incompetence – Before you ever pick up a camera, you are blissfully unaware of your inability to take a photograph! 2. Conscious Incompetence – As you begin to learn the craft, there is a sudden realisation that you know very little about it. 3. Conscious Competence – By this stage, you can methodically use your equipment and compose relatively good images. 4. Unconscious Competence – The neural paths are now well developed. Things like setting up, composition, metering and exposure are being handled by the sub-conscious. Most importantly, one can now concentrate on higher order artistic functions to help with the transmission of hopes, thoughts, fears and desires through the medium.

In terms of personality, I am not sure of how much the project has changed me. For example, when I first jotted down my proposed adventure many years ago, I do recall thinking that it was too big an endeavour for a single individual. However, if I were to do something similar today, I am pretty sure that I would think even bigger! So, in that vein, my tendency to ‘think big’ hasn’t changed at all in the intervening years…

What are your expectations now?

Unfortunately, one of the burdens of being a perfectionist is that I always set my expectations impossibly high. I am striving to release a new book on London fairly soon and also embarking on the sequel to ‘Natural Wonders’; heading off again on another voyage to capture the world cloaked in beauty and fragility.

Separately, I am also cognisant of the relentless advances in photographic technology. Although I’m not sure if I’ll end up shooting the next volume in something ridiculous like holographic format, I do have hopes of remaining at the forefront of this wave.

What reaction would you like to receive from your viewers?

To have inspired others into both photography and environmental conservation would be an honour. More rudimentarily, given the sacrifice behind some of the pictures, a plain old-fashioned ‘wow’ would also be nice!

What is your favourite ingredient for a good photo?

Light is the most important ingredient for the good photo. Period. In this regard, my most favoured condition is the fleeting glimpse of golden light which sometimes occurs through a slit in the clouds at sunset or sunrise. The resulting contrast of rich foreground with brooding blue and ochre clouds is pure photographic manna from heaven, in my opinion.

Can you describe yourself in three words?

Passionate. Panoramic. Perfectionist.

This space is not a question, it’s your free space. Go on, you can say whatever you like,

During the course of my journey, I have been blessed to encounter many like-minded individuals and organisations who are dedicated to the preservation of our areas of outstanding natural beauty. They are too numerous to mention, but World Heritage bodies, environmental organisations and National Park authorities all command my total respect for the work they undertake. Irrespective of where they are based, they have all highlighted to me that man has just as much power to solve problems as he does to create them.

Lastly, I am often asked about the genesis of this project. Why would one commence the long journey to document the natural wonders of the world? In a twist on Mallory’s famous quote, my instinctive answer is: “…because in the future, they may not be there”. I hope this can serve as the salutary ethos behind my body of work.

Bibliography

Natural Wonders: A Panoramic Vision

First published 2009 by Jaspal Jandu Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: 779.3’092

ISBN-13: 9780956081803

Exhibitions

Natural Wonders: A Panoramic Vision (the.oxo@gallery, London, 2009)

A Perfect World (Gallery 77, London, 2008)

Britain on View Exhibition (the.oxo@gallery, London, 2008)

Eyes to Wonder Exhibition (Calumet, London, 2007)

Porsche Collaboration (Dubai, 2006)

Natural Vision (Amman, Jordan 2006)

Awards

[Editors Note: Jaspal Jandu does not voluntarily enter into award competitions. However, he is a member of the International Association of Panoramic Photographers (IAPP) and an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society (ARPS)]

Images included. Note Media Use Only. The copyright, design rights, moral rights and other intellectual property rights in the photographs displayed on herein and on www.jaspaljandu.com are the property of Jaspal Jandu Ltd. The photographs are licensed for use by members of the media solely for the purpose of supporting editorial information provided by the Jaspal Jandu Ltd and by designers and suppliers who have been commissioned by Jaspal Jandu Ltd to produce artwork or other marketing material (the "Permitted Purpose"). Other than for the Permitted Purpose the photographs may not be used, copied, reproduced, downloaded, re-transmitted, distributed or publicised without prior written consent of Jaspal Jandu Ltd.